Using Integrated KT to Successfully Transform Health Service Provision for School-Aged Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder

Cheryl Missiuna, PhD (Principal Investigator)1, Cathy Hecimovich, MEd (Principal Decision-Maker)2, Nancy Pollock, MSc1, Dianne Russell, PhD1, Sheila Bennett, PhD3, John Cairney, PhD1,4, Robin Gaines, PhD1,5, Barbara Ruttan6, Peter Rosenbaum, MD1

1 CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research, McMaster University

4 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neuroscience, McMaster University

2 Central West Community Care Access Centre

5 Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario

3 Brock University

6 Community Rehab/Saint Elizabeth Health Care

Background

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) is a specific motor disability that affects about 5% of all children – or nearly 400,000 children across Canada (APA, 2000). It significantly impacts a child’s ability to complete everyday motor-based academic and self-care tasks such as printing, using scissors, lacing up shoes, opening a lunch bag, and or even sitting at a desk (Missiuna, Moll, King, King, & Law, 2007). DCD is a chronic health condition that cannot be ‘cured’ or ‘fixed’ (Losse et al., 1991). The difficulties of children with DCD often worsen when they enter school and encounter new motor challenges (Forsyth et al., 2007). Without appropriate support, children with DCD, their families, and their educators struggle and become frustrated (Missiuna, Moll, Law, King, & King, 2006). Secondary academic, mental health and physical health issues develop making children’s needs more complex and difficult to cope with over the long term (Cairney et al., 2010; Cairney, Veldhuizen, & Szatmari, 2010; Wang, Tseng, Wilson, & Hu, 2009).

The “Challenge”

In Ontario and other jurisdictions across Canada, intervention for children with DCD is typically provided by occupational therapists (OT) in school settings who conduct one-on-one assessment followed by intervention (most often involving withdrawal of the child from the classroom) to try and change children’s underlying motor impairment (Bayona, McDougall, Tucker, Nichols, & Mandich, 2006). Extensive research has shown that impairment-focused interventions are ineffectual with children with DCD and are an unrealistic focus for school based rehabilitation (Rodger, 2010). Moreover, even if children with DCD are recognized and referred for service, long waitlists mean that many children do not access the health services they need to succeed and participate at school (Deloitte, 2010).

The “Solution”: A Unique Research Partnership using Integrated Knowledge Translation

Concerns about waitlists, frustration with the current system of health service provision, and poor child outcomes prompted the establishment of a partnership between researchers at CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research at McMaster University and a decision-maker from the Community Care Access Centre, the agency that funds school-based occupational therapy services in Ontario. The team recognized that system-level change was needed and partnered to develop an innovative model of school-based service delivery for children with DCD that was evidence-based. Using an integrated approach to KT, we engaged over 60 stakeholders, including school board administrators, teachers, special educators, government policy analysts, health care decision-makers, health care providers and families to share ideas about what type of health service was actually needed to support these children in school settings. Our team conducted a pilot project (2008-09), funded by the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, to determine exactly what type of OT services should be provided. The project was called Partnering for Change to signify the partnerships that were forged between all stakeholders in this effort.

Since this initial study, we have regularly brought together our stakeholders to participate actively in making suggestions, determining the aspects of evaluation that are of interest to them and assisting in interpreting the results (Partnering for Change, 2008; 2009; 2010). Subsequent to the highly successful pilot project, our team received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute for Human Development, Child and Youth Health to conduct a Demonstration Project of our new and innovative model for providing occupational therapy services in schools.

Partnering for Change: An Innovative Model for Providing School-Based Occupational Therapy Services to Children with DCD

The evidence-informed model that emerged from the pilot study has retained the name Partnering for Change (P4C) because it emphasizes the partnership of the health care provider with educators and parents to change the life and daily environment of a child.

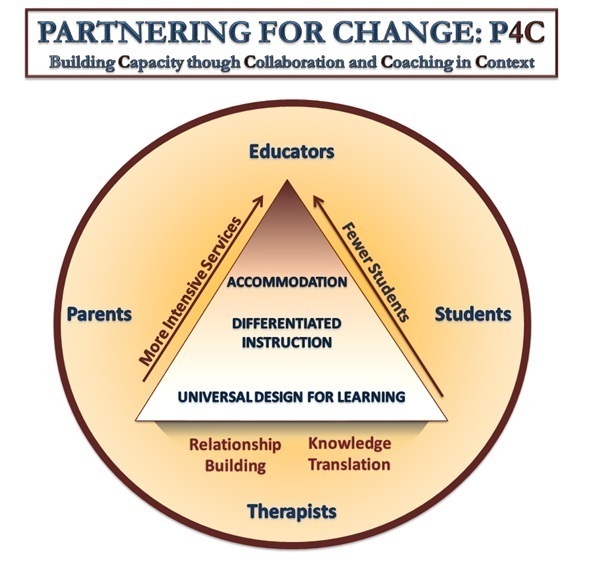

The Partnership focuses on Capacity building through Collaboration and Coaching in Context (Missiuna et al., 2012a). This figure reflects the partnership that is needed between therapists, parents and educators to create environments that will facilitate successful participation for all students. Working from a foundation that focuses on relationship building and sharing of knowledge, these partners collaboratively design environments that foster motor skill development in children of all abilities, differentiate instruction for children who are experiencing challenges and accommodate for students who need to participate in a different way. While the school remains the target of intervention, allowing therapists to impact the greatest numbers of children, therapists are able to increase the intensity of the service that they provide as they coach educators and/or parents about individual students who have more complex needs. In this model, all collaboration and intervention occurs in the context of the school environment.

The goals of this service delivery model are to:

- facilitate earlier identification of children with developmental coordination disorder;

- build capacity of educators and parents to understand and manage the needs of these children;

- improve children’s ability to participate successfully in school and home environments;

- facilitate self and family management in order to prevent secondary disability

Using this new model, the results of our CIHR-funded demonstration project showed that:

- 8 therapists (one day/week) reached over 2600 young students – 230 of whom were identified with motor challenges – and 160 educators in 11 elementary schools (Missiuna et al., 2012b)

- Educators showed positive changes in both knowledge and skills, and were highly satisfied with the service (Missiuna et al., 2012b).

- Educators reported that the strategies they learned from the OT were very practical and feasible, they felt greater confidence in being able to identify DCD and speak to parents about concerns, and they reported carryover of strategies to the next academic year (Missiuna et al., 2012b).

- Parents reported that they were very satisfied with the P4C model and had increased their understanding of DCD. Parents also reported they were more able to effectively support their child by using strategies at home, adapting environments, and sharing information with others (Missiuna et al., 2012b).

- OTs reported a positive change in their beliefs, knowledge and skills (Missiuna et al., 2012b). The therapists also indicated a strong sense of professional growth in this role and reported a feeling of belonging to the school community (Campbell et al., 2012).

- The P4C model facilitated relationship building and collaboration between the OTs and educators (Campbell et al., 2012).

In 2011-12, our team received end-of-grant KT funding from CIHR to translate our findings to our stakeholder constituencies. Stakeholder involvement led to subsequent presentations for, and research proposals to, regional and provincial health care funders. From end-of-grant KT funding, the team also:

- Developed and evaluated an online English parent workshop about DCD (also translated into French)

- Developed and evaluated an online training module for physiotherapists about DCD (also translated into French and a grant was recently received to test its usage in clinical practice in Quebec)

- Developed and refined a series of training modules for occupational therapists delivering P4C

- Developed resource materials to be used in schools with children with DCD

- Developed resource materials for families to use in the community, posted on the CanChild website

What’s next in the P4C “Success Story”?

In 2012, one of our original stakeholders, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, agreed to provide funding to researchers at CanChild – in partnership with the decision-maker with whom we have worked and three Ontario Community Care Access Centres – to implement and evaluate Partnering for Change in 40 schools across 3 regions in Ontario over the next 2 years. With this new funding, the team will: (1) examine outcomes extending from the individual child and family to health and education system levels, (2) determine resource requirements, and (3) make recommendations for large-scale implementation of P4C across Ontario. By adopting an integrated KT approach from the outset, the central theme of “partnering for change” has been infused throughout our research and has helped to make this evidence-based model of school health service provision a genuine story of success.